Understanding Invisible Privilege in India: Caste, Gender, and Religion

Exploring Hidden Privileges in India.

In “My Knapsack of Privilege” (The Indian Express, October 23, 2024), Manoj Jha argues that invisible privileges based on caste, gender, and religion shape access to opportunities and resources in India, leading to systemic inequalities that persist across generations. This essay examines the complexities of these privileges and emphasises the importance of recognising and dismantling them to build a more equitable society.

India, like many other societies, struggles with invisible yet powerful privileges. These privileges, which are often unseen and unacknowledged, are primarily determined by factors like caste, gender, and religion. Together, they create social structures that influence access to education, healthcare, jobs, and overall social mobility. The unequal distribution of these unearned advantages contributes to deep-rooted systemic inequalities. Understanding how these privileges work is essential in addressing the disparities they create and finding ways to dismantle them.

Caste and Privileges in India: The Indian Context

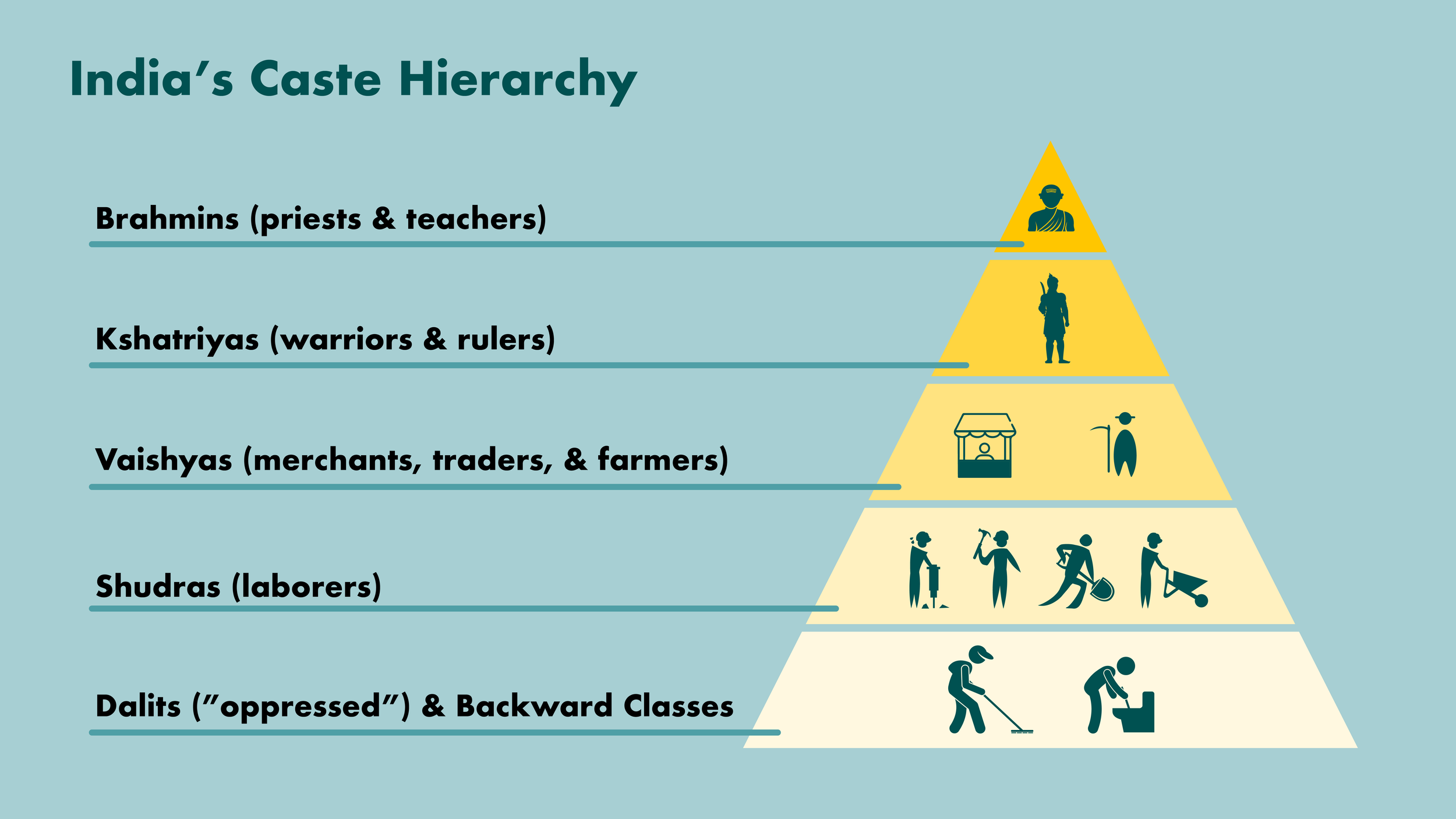

Caste is one of the oldest and most rigid social systems in India. For centuries, the caste system has divided people into hierarchical groups based on their birth, affecting their opportunities and social standing. Invisible Privilege in India in this context operates invisibly, benefiting those from upper castes, particularly Brahmins, while marginalising others. This is similar to the concept of white privilege as described by Peggy McIntosh, who likened unearned advantages to an “invisible knapsack” of benefits carried unknowingly. In India, caste privilege is often unnoticed by those who benefit from it, making it harder to challenge.

B.R. Ambedkar, a renowned social reformer and architect of the Indian Constitution, criticised the caste system for dehumanising those at the bottom while normalising the privileges of those at the top. The normalisation of privilege in upper-caste families ensures that advantages like wealth, education, and social capital are passed down from one generation to the next.

As a result, upper-caste children are more likely to succeed in competitive exams and secure positions in prestigious institutions. On the other hand, disadvantaged communities like Dalits and Adivasis often face limited access to the same opportunities. This cycle of Invisible Privilege in India perpetuates inequality, with each generation of upper-caste families maintaining their advantages, while disadvantaged groups struggle to break free from systemic barriers.

Gender and Privileges in India: Intersectionality in Action

Gender adds another dimension to the complex issue of privilege in India. Women, regardless of their caste or religion, face significant barriers to accessing education, healthcare, and employment. However, when gender intersects with caste or religion, the challenges become even more severe. Feminist scholars often use the concept of intersectionality to describe how different social identities—such as caste, gender, and religion—combine to create unique experiences of disadvantage. This is particularly true for women from excluded groups, such as Dalit and Adivasi women.

For example, Dalit women experience both caste-based and gender-based discrimination, often being confined to the lowest-paying and least desirable jobs. They also face limited access to basic services such as healthcare and education. The intersection of caste and gender compounds their struggles, making it even more difficult to escape poverty and social exclusion. Government programs like Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao aim to improve education for girls, but these efforts often fall short for lower-caste girls due to the multiple barriers they face. Programs designed to address gender inequalities must also take caste into account to ensure they are effective for all women, especially those from sidelined communities.

Moreover, gender privilege is often invisible to men, much like caste privilege. Men may acknowledge that women face gender inequalities, but many fail to recognise their own advantages. For instance, men, especially upper-caste men, often hold positions of power and authority in society, with greater access to education and jobs. This privilege is rarely questioned, and many men remain unaware of how their gender benefits them. Recognising this privilege is crucial to creating a more just and equal society.

Religious Privilege: Majoritarianism in Action

Religion is another key factor in determining privilege in India. Hinduism, particularly upper-caste Hinduism, enjoys significant privilege, while religious minorities—especially Muslims—face systemic discrimination. Hinduism is often seen as the default religion in India, which marginalises those who do not practice it. Religious majoritarianism normalises Hindu privilege, creating advantages for Hindus while excluding others from equal opportunities.

Muslims in India face significant socio-economic disadvantages. The Sachar Committee Report highlighted the stark inequalities faced by Muslims in areas such as education, employment, and healthcare. Muslims often experience discrimination in housing and job markets, where they are frequently denied opportunities based on their religious identity. This exclusion reinforces their marginalisation, much like the systemic discrimination faced by racial and religious minorities in other parts of the world.

In addition to socio-economic marginalisation, religious minorities are also vulnerable to scapegoating during times of crisis. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Muslims were unfairly blamed for spreading the virus, further deepening their social and economic exclusion. Religious privilege, like caste and gender privilege, often goes unrecognised by those who benefit from it. Addressing this requires both individual and institutional efforts to ensure that people of all religions are treated equally in every aspect of society.

The Invisible Knapsack of Privilege: Lessons from McIntosh

Peggy McIntosh’s metaphor of the “invisible knapsack” helps explain how caste, gender, and religious privilege work in India. Those in upper-caste Hindu groups, men, and members of the religious majority carry this invisible knapsack of unearned advantages, often without realising it. These advantages give them easier access to better schools, healthcare, and job opportunities, while under-privileged groups such as Dalits, Adivasis, and Muslims struggle to achieve the same.

McIntosh argues that the first step toward addressing these inequalities is recognising one’s own privilege. This is echoed by social reformers like Ambedkar, who urged privileged individuals to reflect on their advantages and work to dismantle the systems that uphold them. Recognising privilege is essential because it makes individuals accountable for their role in perpetuating inequality. Once this awareness is achieved, individuals can begin to take action to address the structural issues that create and maintain privilege.

Dismantling Privilege: The Path Forward

Dismantling privilege requires both individual action and systemic reform. Privileged individuals must engage with oppressed communities, listen to their experiences, and critically reflect on their own unearned advantages. Reading anti-caste literature and feminist critiques can help individuals better understand how their privileges operate and how they contribute to broader systems of inequality.

Institutional reforms are also crucial. Schools, workplaces, and legal systems must undergo significant changes to ensure that all people, regardless of their caste, gender, or religion, have equal opportunities. For instance, affirmative action policies that aim to increase the representation of subjugated groups in education and employment are a step in the right direction. However, these policies must be implemented effectively to ensure they benefit those who need them most.

Efforts to address privilege should not be limited to token gestures. Instead, they must aim for meaningful change that creates spaces where marginalised groups can thrive on equal terms with historically privileged groups. This requires a fundamental shift not only in individual mindsets but also in the way institutions operate. By addressing privilege at both the individual and systemic levels, it is possible to create a more just and equitable society.

Conclusion

Privilege in India is deeply rooted in systems of caste, gender, and religion. These systems intersect to create a web of advantage for some while excluding others, such as Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims, and women. Recognising these invisible privileges is the first step toward dismantling the hierarchies that perpetuate inequality.

By engaging in self-reflection, open conversations, and institutional reforms, it is possible to build a more just and equitable society for everyone. Privilege may be invisible to those who possess it, but by acknowledging its existence and taking active steps to dismantle it, society can move toward a future where opportunities are truly equal for all.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH