Crawling Carbon Trading Scheme

Context:

India is expected to unveil a new carbon trading regime that will cover less than one-third of its rapidly increasing emissions, possibly by late 2025 or mid-2026.

More on News:

This timeline is nearly three years after its initial approval.

The government approved the establishment of an Indian Carbon Market (ICM) in June 2023.

However, there has been little progress since then, with BEE officials stating they are still finalising the details.

Challenges Ahead:

Time Issues: The benefits of a carbon market typically take time to materialise.

Exclusions: Notably, India is currently excluding heavily polluting sectors, such as electricity and agriculture, from CCTS, which undermines its overall effectiveness.

It is anticipated that any noticeable impact on air quality may not be seen until 2031, as entities participating in CCTS will only represent 30% of the country’s emissions, leaving the remainder unregulated and the atmosphere vulnerable.

Lag Effect: A carbon market usually experiences a “lag effect” of three to five years before it begins to influence emissions.

Delays: The delays in establishing the ICM and addressing emissions are jeopardising India’s commitments to achieving “Net Zero” by 2070.

The ICM is intended to facilitate the operation of a domestic CCTS that aligns with United Nations (UN) regulations and establishes an emissions cap for industries.

Global Emissions at Risk:

On October 28, the UN Climate Change released its 2024 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) Synthesis Report, which evaluates the collective impact of countries’ current climate plans on anticipated global emissions for 2030.

The report painted a grim picture: the NDCs from major polluters like China, the US, and India reflect global emissions of 51.5 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2030 — a mere 2.6% decrease from 2019 levels, and far from the 43% reduction required by that year.

Greenhouse gas emissions at these levels would result in significant human and economic crises for all nations.

By 2035, it is critical to reduce net global greenhouse gas emissions by 60% compared to 2019 to limit global warming to 1.5°C this century.

Current national climate plans are inadequate to prevent global heating from severely impacting economies and threatening billions of lives and livelihoods.

Sector-Specific Exemptions and Future Implications

Electricity is typically the most responsive sector regarding emissions, yet India has excluded fossil fuel power plants from CCTS oversight, and agriculture remains outside its scope.

Framework of the Carbon Trading Programme:

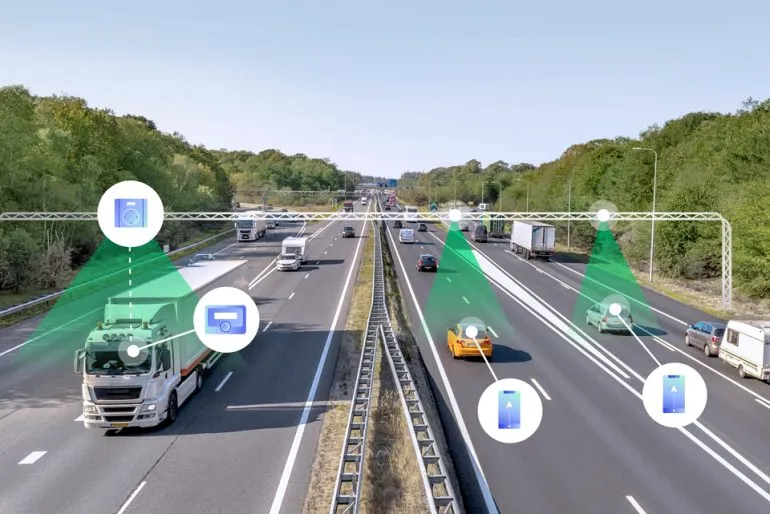

Unlike most programs that monitor total emissions, India’s CCTS will operate on an intensity-based model mandated for energy-intensive industries, where the government will determine emission intensity targets (greenhouse gas emissions per unit of output) for compliance.

Only slight emissions deviations above and below the benchmark will generate credits or deficits.

As India’s GDP has increased, its emissions intensity has decreased over the past two decades.

CCTS should aim for an initial price floor of approximately ₹2,400 per tonne of CO2e (around $30), with prices expected to rise over time, resulting in an annual reduction of about 2.2% in emission intensity from a baseline starting in 2026.

A World Bank official mentioned that buyers prefer low-cost credits, as do nations seeking to fulfil their NDC commitments.

Influence of EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism:

The EU’s controversial Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman described as “unilateral and arbitrary” during a recent event, may motivate Indian officials and industries to expedite the establishment of a carbon market mechanism.

CBAM, which is set to implement a tariff on polluting products entering the EU starting in 2026, has already driven some nations, like Taiwan, to introduce carbon fees in response to industry concerns.

Industry experts have pointed out that CCTS credits can help avoid the impacts of CBAM, ensuring that the associated revenues remain in India.

In fact, fears over CBAM have prompted the steel ministry to grant a trial to Gensol Engineering for a facility powered by green hydrogen for steel production.

Current Carbon Credit Schemes:

India currently operates a domestic carbon credit mechanism known as the Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) Scheme, which awards each renewable generator one certificate for every megawatt-hour of electricity supplied to the grid.

These RECs can be sold to other polluting entities as a form of carbon credit, allowing them to offset their emissions obligations.

The certificates are traded on the Indian Energy Exchange, with utilities utilising them to fulfil their renewable purchase obligations (RPOs).

However, industry officials have reported that the REC scheme has faltered, with certificate prices plunging from approximately ₹1,000 in January 2023 to around ₹112 now.

This price drop allows utilities to meet their RPOs at a minimal cost.

Additionally, the scheme excludes traders, aggregators, and investors, permitting only actual users to participate.

A World Bank study indicates that the minimum carbon price should be set at $40-$60 per tonne by 2025 and around $100 per tonne by 2030 to achieve current global NDC targets. In stark contrast, India’s RECs currently trade at just above a dollar, while voluntary credits are fetching approximately $1.50 per tonne.