Maratha Administration System

Maratha Administration System

The Maratha Empire, founded by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in the mid-17th century, marked a significant departure from both the medieval Deccan sultanate models and the imperial Mughal system, evolving into a distinctive polity that combined Hindu political ideas with pragmatic governance structures. Shivaji’s administrative framework laid the foundation for efficient governance, sustained revenue collection, and a disciplined military that underpinned Maratha expansion and stability.

1. Historical Context and Foundation of Maratha Administration

Shivaji rose in the Deccan at a time of political fragmentation, where central authority was contested, and local governance was often weak. Responding to chaotic rule and foreign dominance, especially that of the Mughal and Adil Shahi regimes, Shivaji established an independent Maratha state grounded in the concept of Hindavi Swarajya — the self-rule of his people. His coronation in 1674 at Raigad symbolised the formal beginning of a sovereign administrative system.

Through his reforms, Shivaji emphasized direct rule, merit-based appointments, and state accountability to subjects — principles very different from the hereditary and feudal norms prevalent in much of South Asia. Centralised authority remained combined with decentralised execution, where local institutions maintained a crucial role in governance.

2. Nature of the Maratha State

The Maratha system under Shivaji was essentially a centralised autocratic monarchy in theory, with the Chhatrapati (king) as the supreme authority. However, the effectiveness of the system lay in its functional decentralisation, where appointed officials at provincial, district, and village levels executed the policies of the central government.

Unlike many coexisting states that relied on Persian bureaucratic norms, the Marathas used Sanskritised administrative terminology and consciously adopted Marathi as the official state language to strengthen regional identity and administrative coherence. Shivaji even commissioned works to formalise a statecraft lexicon.

3. The Central Administration

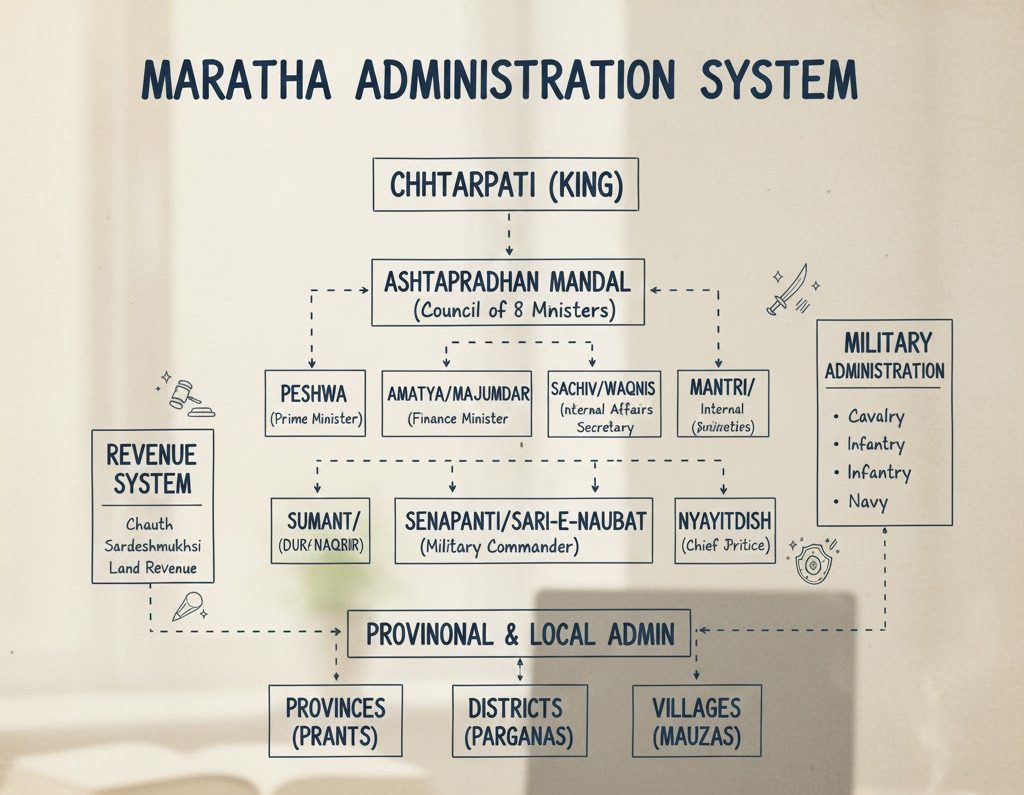

Central administration in Shivaji’s system was designed to aid the monarch in governance, policy decisions, and statecraft. Its most prominent feature was the Ashta Pradhan Mandal — the Council of Eight Ministers. Each minister had clearly defined responsibilities, reflecting a deliberate distribution of power to avoid administrative concentration in a few hands.

3.1 The Ashta Pradhan

The council comprised the following offices, with portfolios aligned to state functions:

- Peshwa (Pantpradhan): The Prime Minister, responsible for overall state administration.

- Amatya (Mazumdar): Chief finance minister and head of revenue administration.

- Sachiv (Surunavis): Secretary responsible for royal correspondence and record keeping.

- Sumant (Dabir): Foreign minister, dealing with external relations.

- Senapati (Sar-i-Naubat): Commander-in-Chief, in charge of military organisation and defence.

- Nyayadhish: Chief Justice, overseeing judicial decisions.

- Panditrao: Head of religious affairs, sanctioning ceremonies and state religious policy.

- Chitnis: Personal secretary managing documentation and communication.

This council symbolised a systematic bureaucracy where administrative functions were institutionalised and separate from purely military leadership. Except for the Senapati, all ministers were primarily civilian officials, indicating Shivaji’s emphasis on governance as distinct from warfare.

The Ashta Pradhan system was not static — later developments under the Peshwas showed evolution in ministerial prominence, with the Peshwa position gradually becoming the de facto executive head of the Empire, especially after Shahu’s reign.

4. Provincial Administration

To manage the expanding realm effectively, Shivaji divided his kingdom into administrative units:

- Prants: Provinces or large territorial units.

- Parganas/Tarafs: Sub-divisions of Prants, similar to districts.

- Mauza: The smallest administrative unit, typically a village cluster.

In Maratha Administration, each province was overseen by governors and administrators who reported to the central authority. Officials like Deshmukhs and Deshpandes maintained law and order and revenue collection in their areas. The Havaldar was the chief district administrator reporting to the hierarchy.

This layered structure was intended to ensure accountability and local oversight, enabling the central government to remain informed about local conditions and challenges. Regular inspection and avoidance of hereditary office holding prevented decentralised authority from becoming entrenched.

5. Revenue Administration

In Maratha Administration, the economic health of the Maratha state rested on a well-defined revenue system that balanced state needs with agrarian welfare. Revenue administration under Shivaji followed a two-pronged approach — direct tax collection and supplementary levies.

5.1 Direct Land Revenue

Shivaji adopted and adapted the Kathi system of land measurement from earlier Deccan sultanates, in which land was measured with a rod (kathi) to calculate state demand fairly. Farmers (ryots) paid land revenue directly to the state, avoiding exploitation by intermediaries such as powerful Zamindars.

In Maratha Administration, this was effectively a Ryotwari system, ensuring that the government dealt directly with cultivators, and the system was recorded meticulously to minimise corruption and arbitrariness.

5.2 Chauth and Sardeshmukhi

Two innovative revenue instruments distinct to Maratha polity were:

- Chauth: A levy amounting to one-fourth (25%) of the revenue from territories not directly governed by the Marathas. This was effectively a protectorate or protection tax, in return for not raiding those territories and potentially offering military assistance.

- Sardeshmukhi: An additional 10% revenue claim, often justified as the hereditary right of the Marathas over Deccan lands, asserting their traditional overlord status.

Together, Chauth and Sardeshmukhi became major revenue sources and also instruments of political assertion beyond formal Maratha dominions.

5.3 Other Revenue Streams

In Maratha Administration, revenue also came from customs, excise, transit duties, grazing taxes, and forest produce — ensuring diversification of income and resilience against agrarian shocks. Shivaji also ensured that revenue demands were humane — taxes could be paid in money or kind, and exceptions were made in times of drought or famine.

6. Judicial System

Judicial administration under the Marathas blended traditional community mechanisms with formal courts. At the village level, disputes were resolved by Panchayats under the oversight of the Patel or village headman. More serious civil and criminal cases were heard at higher levels, with the Nyayadhish dispensing justice in towns and urban centres.

In Maratha Administration, the legal framework drew heavily on ancient Hindu law texts like the Manusmriti and Yajnavalkya Smriti, shaping both civil and criminal jurisprudence.

7. Military Administration

A hallmark of Maratha governance was the integration of military efficiency within the administrative system. Shivaji’s geographic context — rugged terrain and numerous forts — necessitated a well-organised army capable of sustained campaigns and rapid deployment.

7.1 Army Organisation

The Maratha army comprised:

- Infantry: Including the formidable Mavali foot soldiers adept at mountain warfare.

- Cavalry: Highly mobile horsemen forming the core of rapid strike capacity.

- Navy: An innovative force established by Shivaji for coastal defence and trade protection.

Shivaji ensured that soldiers were paid in cash rather than land grants to reduce dependence on feudal intermediaries, creating a professionalised military labour force. Officers and commanders often received Saranjam — land or revenue assignments — to maintain loyal service.

7.2 Fort Administration

Forts were administrative and strategic centres staffed by officers such as:

- Havaldar: Keeper and commander of the fort.

- Sabnis: In charge of accounts and correspondence.

- Karkhanis: Responsible for stores and logistics.

This ensured that each fort functioned as an autonomous administrative unit, capable of holding territory independently while remaining part of the larger polity.

8. Later Developments: Peshwa Era and Confederacy

After Shivaji’s death and during the succession of rulers like Sambhaji and Rajaram, the centralised administrative model faced challenges, eventually evolving into a confederacy under the authority of the Peshwas. The Peshwa, initially the chief minister, became the de facto executive authority, especially during Shahu’s reign and thereafter.

Under the Peshwas, the central secretariat known as Huzur Daftar at Poona coordinated civil, military, and revenue affairs across the confederacy, reflecting a more bureaucratic and layered governance structure.

The confederacy system allowed semi-independent Maratha chiefs — such as the Scindias, Holkars, and Gaekwads — to manage territories while owing military support to the Peshwa. This flexible political structure enabled the Marathas to influence large parts of the Indian subcontinent in the 18th century.

9. Legacy and Assessment

The Maratha administration under Shivaji blended indigenous political values with practical governance needs. Its key strengths included:

- Emphasis on direct revenue collection from cultivators, reducing exploitation.

- Professionalised military administration.

- Clear separation of military and civil functions within the bureaucracy.

- Use of administrative units and officials to ensure local representation and accountability.

- Adaptation and evolution under the Peshwa confederacy to accommodate the needs of a growing and diverse polity.

Shivaji’s system, therefore, stands out in medieval Indian history for its focus on welfare, efficiency, and integration of civil and military governance — features that influenced later Indian administrative traditions.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH