Reforming Election Nominations: Law, Rights, and Technology

Analytical essay on India’s electoral nomination reforms, highlighting Kannan Gopinathan’s critique of arbitrary rejections, legal gaps, and the potential of digital solutions for transparency and fairness.

Reforming Election Nominations: Law, Rights, and Technology – Electoral Reforms in India

In “Why the Nomination Process Needs Reform” (The Hindu, November 07, 2025), Kannan Gopinathan argues that India’s electoral nomination system—meant to ensure fair competition—has instead become a gatekeeping mechanism riddled with arbitrary decisions, outdated procedures, and unnecessary hurdles. His call for reform reflects a larger democratic concern: the nomination process, which should open the door to political participation, too often shuts it. This essay seeks to argue that the nomination process in India urgently needs reform. It must replace excessive official discretion and complex procedures with clear legal safeguards and technological transparency, ensuring that every eligible citizen can contest elections on an equal footing.

Legal Ambiguity Hurts

Under India’s Representation of the People Act, Returning Officers (ROs) hold vast powers to accept or reject nomination papers. Section 36 allows them to reject a candidate’s nomination if it contains “defects of a substantial character.” The problem lies in the phrase’s vagueness—there is no clear legal definition of what constitutes a “substantial defect.” This ambiguity gives officials enormous discretion, opening space for bias and misuse.

Even more troubling is Article 329(b) of the Constitution, which bars courts from intervening in election matters until after voting concludes. This means that if a nomination is wrongly rejected, the affected candidate cannot seek immediate justice. By the time the courts can review the matter, the election is over. In effect, one official’s subjective decision can end a candidacy before it even begins.

This system flips democratic logic on its head. The right to contest elections, which flows naturally from the right to vote, is treated not as a guarantee but as a privilege. Instead of the state having to justify exclusion, candidates must prove their compliance down to the smallest detail. This reversal undermines fairness, reduces political competition, and restricts the electorate’s freedom to choose among genuine contenders.

Procedural Barriers Rise

India’s nomination process, once meant to ensure transparency, has become overloaded with rules and formalities. Though intended to promote honesty in elections, these layers of procedure now create confusion, technical rejections, and unfair barriers that limit candidates’ ability to contest freely.

Candidates must complete numerous tasks—take oaths before specific officials within narrow time frames, notarise affidavits flawlessly, and secure no-dues certificates from multiple departments. A single error, missing stamp, or delay can invalidate an entire nomination. These strict procedures often punish candidates, especially independents and opposition members, who lack administrative support. Bureaucratic complexity, combined with the wide discretion of Returning Officers, transforms what should be a democratic opportunity into an exclusionary filter, undermining both fairness and the spirit of free elections.

Such procedural traps silence potential representatives before voters even see their names on the ballot. Genuine participation becomes hostage to technicalities, delays, and bias. Streamlining requirements, setting clear correction periods, and reducing discretionary power are vital to restore faith in nominations as the first true step of democracy.

Fairness Through Clarity

True reform begins with clear definitions of what counts as a serious nomination error. By separating minor paperwork issues from genuine legal disqualifications, the system can move from arbitrary exclusion toward fairness, ensuring candidates are judged on substance, not technicalities.

Nomination flaws should be grouped into three categories. Technical defects—like missing signatures or incomplete affidavits—should be fixable within a short correction window. Verification defects, such as disputed documents, require proper investigation before rejection. Constitutional or statutory disqualifications—for example, age or citizenship violations—should be the only grounds for outright exclusion. Every rejection must include written reasons and supporting evidence, ensuring transparency and consistency. Such clarity limits misuse of discretion and promotes fairness in election administration, protecting both candidates and voters alike.

Reform must also shift the burden of proof back to the state. Candidates should have a presumed right to contest, with officials required to justify any exclusion under clear legal grounds. This change restores balance, ensuring nomination scrutiny upholds the Constitution’s democratic promise of equal and genuine participation.

Facilitating Over Filtering

Other democracies provide valuable lessons in making nomination systems fair and inclusive. In the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and Australia, election authorities see themselves as facilitators, not gatekeepers. When a candidate makes a clerical error, they are notified promptly and given time—often 48 hours or more—to fix it. Officials even provide guidance on how to correct the issue.

These countries also allow multiple levels of appeal, ensuring no one is unfairly excluded due to a simple mistake. The emphasis is on helping candidates comply, not catching them out.

Adopting such a model in India would shift the culture of election administration from suspicion to support. Election officers would act as partners in the democratic process—helping citizens exercise their rights, not preventing them from doing so. This shift is crucial if India is to live up to its claim of being the world’s largest democracy.

Technological Reforms

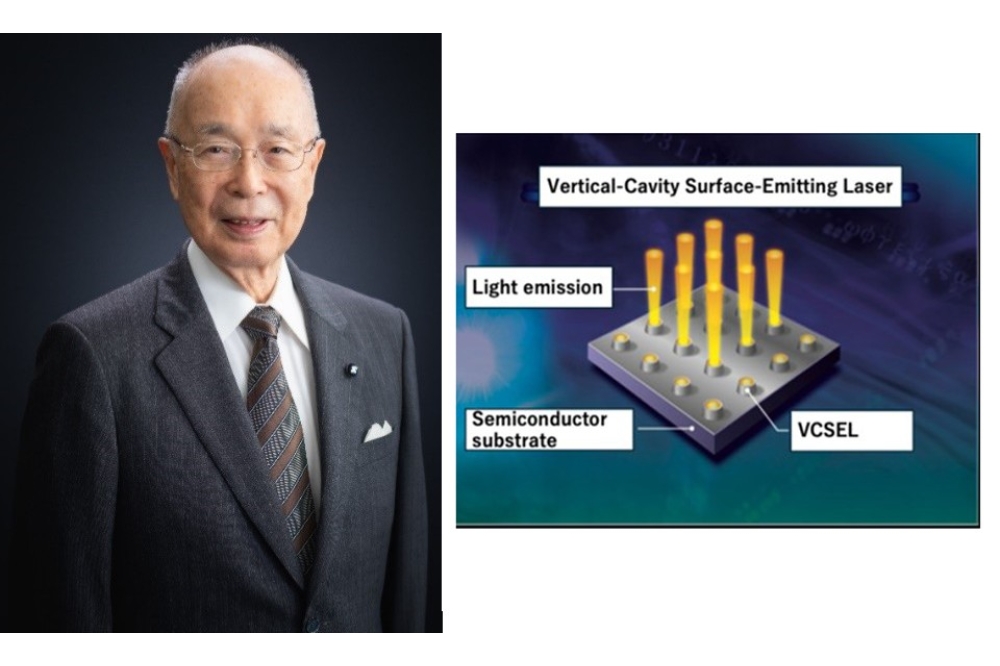

Technology can address many of the problems that plague the current system. A digital-by-default nomination platform—linked to the Election Commission’s existing voter database—could make the entire process transparent, efficient, and user-friendly.

Such a system would allow candidates to:

- File nominations online, including uploading affidavits and documents.

- Take digital oaths and make e-payments for deposits.

- Verify voter ID, age, and constituency automatically.

- Receive instant notifications about errors or missing information.

- Make real-time corrections before deadlines close.

Automation would eliminate most human errors—misspelled names, mismatched entries, or incomplete forms. It would also prevent officials from rejecting nominations for trivial or politically motivated reasons.

Moreover, a public dashboard could display the status of all nominations—when they were filed, whether any corrections were requested, and the reasons for acceptance or rejection. This would make the process visible to everyone, building trust and accountability.

Digital records would also create audit trails, deterring misuse of power. Every decision would leave a timestamped digital footprint, discouraging arbitrary behaviour and making it easier to review disputed cases later.

However, technology must remain inclusive. Physical submissions should still be allowed to ensure that candidates in rural or low-connectivity areas are not disadvantaged. The goal is not to replace human access but to enhance it with efficiency and fairness.

Digital Legal Synergy

Legal and technological reforms must work together to make nominations fair and transparent. While strong laws protect rights, digital systems ensure those laws are applied consistently, transforming a slow, paper-heavy process into a modern, accessible gateway for democratic participation.

Technology can give real force to legal safeguards. For instance, digital nomination platforms could automatically record and publish reasons for any rejection, citing the relevant legal provisions. Built-in correction windows would allow candidates to fix errors within set time limits, reducing arbitrary exclusions. Automated logs and audit trails would make every official action traceable, boosting accountability. When combined with clear legal standards, such innovations replace opacity with transparency and ensure fairness from the very first step of the electoral process.

This integration protects two central democratic rights: the citizen’s right to contest and the voter’s right to genuine choice. When technology enforces fairness and law guarantees equality, democracy becomes more than a promise—it becomes a lived, everyday reality where every eligible voice can freely seek representation.

Conclusion

India’s nomination process, designed to protect election integrity, often weakens it through excessive discretion, unclear laws, and needless bureaucracy. Legitimate candidates face rejection over trivial errors, narrowing voter choice and damaging public faith in democratic fairness and equal opportunity.

Reform is both urgent and possible. It should rest on three key pillars: clarity in law, defining genuine disqualifications with written, evidence-based decisions; facilitation in procedure, where officials guide rather than block candidates; and transparency through technology, using digital systems for verification, feedback, and audit trails. These principles ensure that every qualified citizen can contest fairly, and that the process remains open, accountable, and free from political manipulation. Together, they safeguard democracy’s foundation—equal participation for all.

By modernising nomination scrutiny with fairness and technology, India can restore trust in its elections. A transparent, accessible system that encourages participation instead of exclusion will make democracy stronger and more inclusive. When every citizen’s right to contest is treated as sacred, democracy does not merely survive—it thrives.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH