Where is India’s SO₂ Control from Thermal Power Plants Headed?

India’s SO₂ Control from Thermal Power Plants.

This essay joins the discussion on flue gas desulfurisation (FGD) installations in India’s thermal power plants, a topic highlighted in Shreya Verma’s article, “Where is India’s SO₂ Control from TPPs Headed? NITI Aayog’s Memo over FGDs Fuels Debate,” published in DownToEarth on October 25, 2024. It focuses on the future of FGD technology in these plants, exploring whether FGDs are necessary for protecting health and the environment or if they are simply a costly requirement with limited benefits.

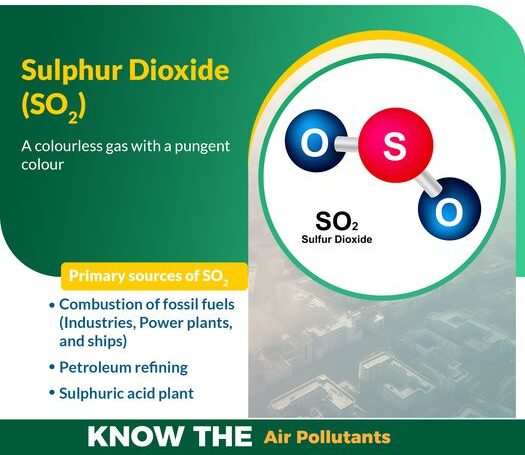

India has relied on coal-based thermal power plants for decades, with these plants producing a significant portion of the country’s electricity. However, coal combustion releases sulphur dioxide (SO₂), a pollutant harmful to both human health and the environment. To control these emissions, India has turned to flue gas desulfurisation (FGD) technology, which captures and removes SO₂ from the exhaust gases of power plants.

Recently, a debate has erupted over whether the widespread installation of FGDs is necessary, sparked by a memorandum from NITI Aayog, a public policy think tank, recommending a pause on FGD installations. This debate has brought to the forefront questions about environmental safety, financial burdens on energy production, and whether FGDs are indeed effective in reducing harmful emissions.

Background on SO₂ Emissions and FGDs in India

SO₂ is a toxic gas released when coal is burned, contributing to acid rain, respiratory diseases, and environmental damage. India is one of the world’s largest SO₂ emitters, largely because its coal-based power plants release significant amounts of this pollutant. Recognising the harmful impacts of SO₂, the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) mandated the installation of FGDs in thermal power plants in 2015. These systems reduce SO₂ emissions by 90% or more, converting it into by-products like gypsum, which can be used in construction.

FGDs come with challenges. They are costly, at Rs 1 to 2 crore per megawatt, and require significant space and technical adjustments, especially in older plants. The estimated cost of FGD installation leads to higher electricity production costs, potentially impacting consumers. As a result, only a small fraction of India’s power plants has implemented FGD technology. Meanwhile, some experts argue that Indian coal, with its relatively low sulphur content, doesn’t require FGDs on the same scale as coal in other countries.

The NITI Aayog Report and the Debate Over FGDs

The debate over FGD installation was intensified by a recent memorandum from NITI Aayog, which drew on a report by the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research-National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (CSIR-NEERI). According to CSIR-NEERI, SO₂ emissions from India’s thermal power plants do not significantly affect ambient air quality, suggesting that the requirement for FGDs could be paused. The report noted that most power plants meet SO₂ emission standards and argued that regulatory focus should shift to controlling particulate matter (PM), another pollutant with severe health impacts.

However, this recommendation has faced opposition. Critics, such as the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), claim that India’s high SO₂ levels pose a serious public health risk, especially given that India emits almost twice as much SO₂ as China. They argue that FGDs are essential to reducing these emissions and protecting public health. Further complicating matters, a separate study from the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) Delhi suggested that phased FGD installations are necessary to meet emission norms, contradicting the CSIR-NEERI’s conclusions.

Environmental and Health Implications of SO₂ Emissions

SO₂ pollution has far-reaching environmental and health consequences. In the environment, it combines with water vapor to form sulfuric acid, which falls as acid rain, damaging crops, water bodies, and buildings. In humans, SO₂ exposure can cause respiratory illnesses, such as asthma and bronchitis, and has been linked to heart disease and premature death.

High SO₂ levels also contribute to particulate matter formation (PM2.5 and PM10), which can penetrate deep into the lungs, causing long-term health issues. India’s large population, particularly in regions like the Indo-Gangetic Plain, is vulnerable to the impacts of high SO₂ levels. Studies have shown that areas close to thermal power plants experience higher rates of respiratory illnesses, underscoring the need for emission controls.

Economic Concerns and Implementation Challenges

FGD installations are not only expensive but also difficult to implement. The cost of installing FGDs is high, and these systems require maintenance and periodic updates, further increasing expenses. India’s power sector argues that the cost of installing FGDs is an unfair burden on coal-based power plants, which may raise electricity prices for consumers. Furthermore, due to limited domestic manufacturing capacity, India relies on imported components for FGD systems, which can cause delays and increase costs.

Another issue is the inconsistency in regulatory enforcement. Since 2015, multiple extensions have been granted for FGD installation deadlines, leading to a lack of urgency among power plant operators. This inconsistency undermines the effectiveness of emission regulations and contributes to slow FGD adoption.

Arguments For FGD Installations

- Health Benefits: Installing FGDs would reduce SO₂ emissions, leading to cleaner air and reducing health risks. Lowering SO₂ levels could reduce cases of asthma, heart disease, and other respiratory issues, especially in highly polluted regions.

- Environmental Protection: FGDs would help protect ecosystems from acid rain and other environmental damage. Reducing SO₂ emissions would contribute to less acidification of soils and water bodies, promoting biodiversity.

- Compliance with International Standards: Countries like China have already implemented FGDs on a large scale. Implementing FGDs in India would bring the country closer to international environmental standards, demonstrating commitment to sustainable energy production.

- Economic Opportunities: The gypsum byproduct from FGD processes can be sold, offsetting some of the costs of installation and providing a potential revenue stream for power plants.

Arguments Against FGD Installations

- High Costs: FGD installation is expensive, with costs estimated at Rs 1-2 crore per megawatt. This could increase electricity costs, impacting consumers and potentially slowing economic growth.

- Limited Impact on Air Quality: The CSIR-NEERI report claims that SO₂ emissions from TPPs have a minimal impact on ambient air quality. This raises the question of whether the financial burden of FGD installations is justified if they don’t significantly improve air quality.

- Challenges with Domestic Manufacturing: India’s reliance on imported FGD components has caused delays in implementation. Scaling up domestic manufacturing to meet demand would require time and investment.

- Alternative Pollution Control Methods: Some experts suggest that focusing on particulate matter and nitrogen oxides may be more effective in improving air quality. Reducing PM2.5 and PM10 emissions, which also contribute to haze and respiratory issues, could be achieved through measures other than FGD installations.

Moving Forward: Possible Solutions

Given the complex nature of this issue, a balanced approach may be the best path forward. Some potential solutions include:

- Targeted FGD Implementation: Installing FGDs in plants located near high-population or high-pollution areas could address health risks while limiting costs. For example, power plants within a 10 km radius of cities with large populations or critically polluted areas could prioritise FGD installations.

- Incentives for Cleaner Technology: The government could offer subsidies or tax breaks to power plants that install FGDs, offsetting some of the financial burden. Alternatively, investing in renewable energy sources like solar and wind power could reduce dependence on coal and lower overall SO₂ emissions.

- Stronger Regulation and Enforcement: Establishing clear, enforceable deadlines and penalties for non-compliance could encourage faster FGD adoption. Regulatory consistency would create a more predictable environment for power plant operators, helping them plan and implement necessary changes.

- Public Awareness and Health Initiatives: Educating the public about the health risks of SO₂ and encouraging community support for cleaner air initiatives can build a case for FGD installations. Additionally, health programs targeting communities near TPPs could help mitigate the impacts of air pollution.

- Improved Emissions Monitoring: Implementing a robust, transparent emissions monitoring system would allow for real-time assessment of SO₂ and other pollutants. Accurate data can inform policy decisions and help regulators determine which plants need FGDs most urgently.

Conclusion

The debate over FGD installations in India’s thermal power plants highlights a critical intersection between environmental protection, public health, and economic realities. While the costs of FGDs are high and the implementation challenging, the benefits in terms of cleaner air and healthier communities are undeniable. Pausing FGD installations based on incomplete or inconclusive studies may risk public health and environmental stability. Instead, a balanced, targeted approach—focusing on high-priority areas and providing financial incentives—could provide a path forward. As India navigates this issue, the decisions made will shape the country’s air quality, energy landscape, and commitment to sustainable development for years to come.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH