The Ken-Betwa Link Project: Balancing Promises and Challenges

The Ken-Betwa Link Project.

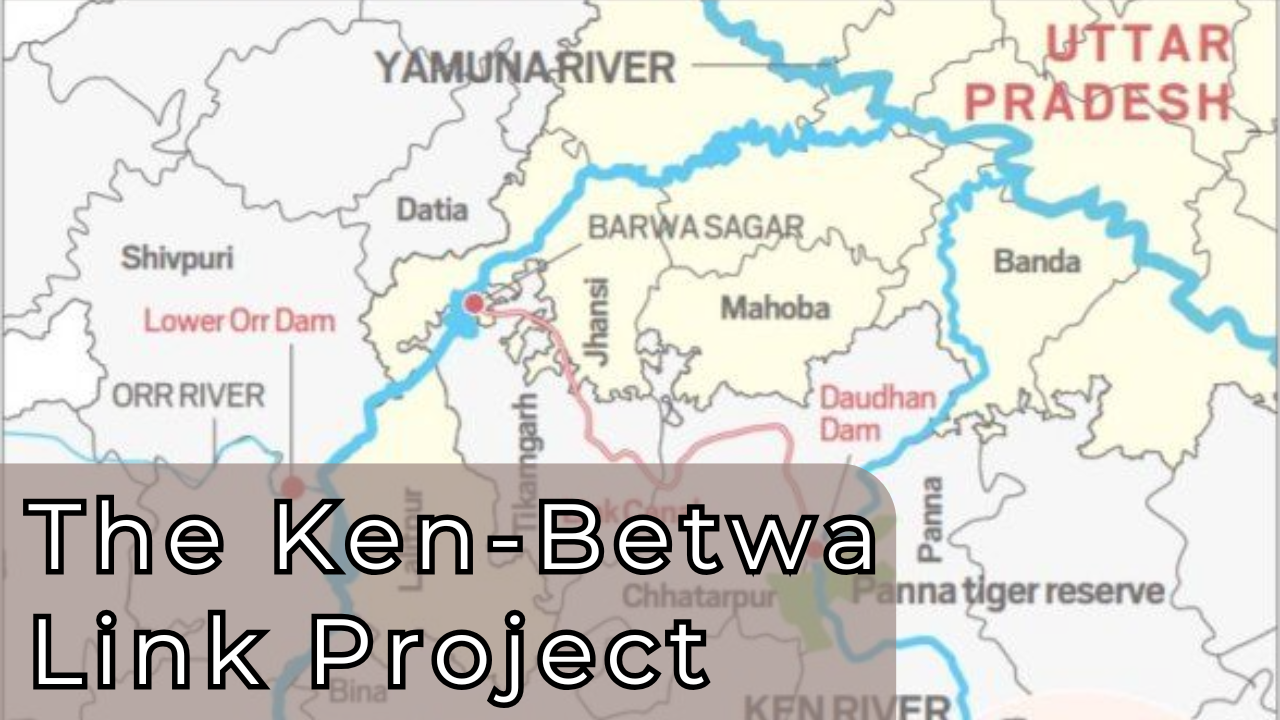

The KBLP is a key initiative under India’s National River Linking Project (NRLP), aimed at tackling water scarcity in Bundelkhand, a region spanning Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Conceptualised in the 1980s and formally approved in 2021, the project plans to transfer water from the Ken River, classified as “surplus,” to the Betwa River through a 221-kilometre canal, a 2-kilometre tunnel, and the Daudhan Dam. Estimated to cost ₹44,605 crore, the KBLP is expected to irrigate 10.62 lakh hectares of farmland, supply drinking water to over 6.2 million people, and generate 130 megawatts of renewable energy.

Bundelkhand has long suffered from droughts, depleting groundwater, and poor irrigation facilities. For its people, the KBLP offers the hope of a revived economy and improved living conditions. However, the project has sparked fierce debate due to its potential environmental, social, and hydrological consequences. Critics warn of significant deforestation, displacement of communities, and disruption to ecosystems, raising questions about the feasibility and sustainability of this ambitious project.

Socio-Economic Aspirations

The KBLP is projected to bring socio-economic transformation to Bundelkhand, a region plagued by poverty and underdevelopment. Reliable water supply is considered a game-changer for the area’s predominantly agrarian economy. By irrigating over 10 lakh hectares of farmland, the project could stabilise crop yields and encourage farmers to grow a wider variety of crops, including cash crops. This diversification would not only increase farmers’ incomes but also enhance food security and reduce dependency on the unpredictable monsoon rains.

Additionally, the project promises to provide drinking water to 6.2 million people across Bundelkhand. This could improve public health by reducing waterborne diseases, which are common in areas with inadequate water supplies. Access to clean water may also reduce rural-to-urban migration, enabling communities to stay in their hometowns rather than seeking livelihoods in cities.

Moreover, the KBLP’s plan to generate 103 megawatts of hydropower and 27 megawatts of solar energy aligns with India’s renewable energy goals. The inclusion of clean energy production in the project highlights its potential to not only support regional development but also contribute to India’s larger efforts to combat climate change. Together, these benefits make the KBLP appear as a beacon of hope for Bundelkhand, promising to uplift millions of lives.

Environmental and Ecological Costs

While the socio-economic benefits of the KBLP are significant, the project’s environmental costs are equally substantial. One of the most controversial aspects is its impact on the Panna Tiger Reserve, which will lose approximately 4,500 hectares of forest to the construction of the Daudhan Dam. This reserve is home to endangered species such as tigers, leopards, and gharials, and has been a conservation success story after tigers were reintroduced following their local extinction. Critics argue that the project could fragment wildlife habitats, forcing animals to migrate to already overburdened neighbouring forests, increasing human-wildlife conflicts.

The environmental impact extends beyond the tiger reserve. The submersion of 9,000 hectares of land for the dam will result in significant deforestation, leading to biodiversity loss and disrupting local ecosystems. The loss of forest cover will also reduce carbon sequestration, accelerating climate change. Furthermore, downstream ecosystems such as the Ken Gharial Sanctuary are at risk of being disrupted due to altered water flows and sedimentation patterns. This could threaten the survival of gharials and freshwater turtles, further compounding the ecological damage.

Hydrological Feasibility

The KBLP’s hydrological basis has come under scrutiny, as its feasibility depends on the assumption that the Ken River has surplus water to spare. However, local studies and observations suggest otherwise, with reports indicating seasonal variability and frequent water shortages in the Ken basin. Critics warn that transferring water from the Ken to the Betwa River could worsen scarcity in the Ken basin, especially during dry years, undermining the project’s core objective of solving regional water imbalances.

The large-scale infrastructure planned for the project also poses risks to the natural flow of rivers. The Daudhan Dam and the canal network could disrupt sediment transport, groundwater recharge, and the overall morphology of the rivers. These changes could have wide-ranging effects, including reduced agricultural productivity and harm to downstream ecosystems. Moreover, concerns about water quality arise from the potential for sedimentation, erosion, and pollution within the canal system, which could affect the usability of the water transferred to the Betwa basin.

Social Displacement and Marginalisation

One of the most significant social costs of the KBLP is the displacement of communities in the project-affected areas. The construction of the Daudhan Dam will submerge ten villages, displacing over 5,000 families. Many of these families belong to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, who rely heavily on agriculture, fishing, and forest resources for their livelihoods. For these marginalised groups, displacement represents not only an economic loss but also a disruption of their cultural and social identities.

India’s history with resettlement and rehabilitation programmes offers little reassurance. Displaced communities often receive inadequate compensation and are relocated to areas with limited access to basic amenities like water, healthcare, and education. Without proper support, many affected families may find themselves in deeper poverty and vulnerability.

Water-sharing disputes between communities add another layer of complexity to the project. The diversion of water from the Ken River to the Betwa River could ignite tensions, as communities in the Ken basin may perceive the project as depriving them of their rightful resources. Such conflicts undermine the project’s goal of equitable water distribution and highlight the importance of addressing local concerns in its planning.

Flaws in Planning and Governance

The planning process for the KBLP has faced widespread criticism, particularly for its lack of transparency and inadequate assessment of impacts. The feasibility report prepared by the National Water Development Agency (NWDA) has been criticised for failing to provide robust data on water availability, environmental consequences, and displacement costs. Critics argue that the assumption of wildlife migrating naturally to other habitats ignores the complexities of ecosystem balance and lacks scientific evidence.

Moreover, the decision-making process has excluded key stakeholders, including local communities, environmental experts, and civil society organisations. This top-down approach has eroded trust in the project and raised questions about its legitimacy. Without meaningful engagement with affected communities and other stakeholders, the KBLP risks overlooking critical nuances that could lead to unsustainable outcomes.

Exploring Alternatives

Given the significant challenges associated with the KBLP, alternative approaches to addressing water scarcity should be considered. Techniques like rainwater harvesting and groundwater recharge offer sustainable solutions that do not require large-scale infrastructure. These methods can help communities capture and store water locally, reducing dependence on external water transfers.

Improved irrigation practices, such as drip and sprinkler systems, can minimise water wastage and maximise agricultural productivity. Watershed management, which involves restoring and protecting catchment areas, can enhance water availability while preserving local ecosystems. These approaches are cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and emphasise community participation, empowering local stakeholders to take ownership of water management.

Broader Implications for India’s River Linking Programme

As the pilot project under the NRLP, the KBLP’s success or failure will have far-reaching implications for the future of river linking in India. If the project delivers its promised benefits while mitigating its adverse impacts, it could serve as a model for similar initiatives aimed at addressing regional water imbalances. Conversely, if the KBLP falls short of its objectives or causes significant harm, it could prompt a re-evaluation of the viability of large-scale river linking as a strategy for water resource management.

The KBLP’s outcome will also influence India’s approach to balancing development with environmental and social sustainability. Lessons learned from this project could shape future policies and ensure that water management initiatives are more inclusive, equitable, and ecologically sensitive.

Conclusion of The Ken-Betwa Link Project

The Ken-Betwa Link Project exemplifies the complexities of balancing development with conservation. While it offers hope for improved irrigation, drinking water supply, and renewable energy generation, the project’s environmental, social, and hydrological costs cannot be ignored. The loss of biodiversity, displacement of communities, and potential disruption to river ecosystems underscore the need for more comprehensive planning and participatory governance

To ensure that the KBLP achieves its goals without causing irreversible harm, it is essential to address its shortcomings and explore alternative approaches to water management. By doing so, India can create a model for sustainable development that harmonises economic growth with ecological and social equity. The outcome of the KBLP will not only determine the future of Bundelkhand but also shape the nation’s broader water management strategies, making it a project of national and global significance.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH